The world is still barreling in the wrong direction on coal power plant construction, and China — despite its pledges to scale down fossil fuels to avert climate catastrophe — continues to drive that trend.

China built the majority of the coal plants completed in 2024, and also accounted for 85 percent of the world’s new coal plant proposals, according to a report out Monday by Global Energy Monitor, an environmental research and advocacy group. That means instead of transitioning away from coal power — the source of nearly 40 percent of China’s carbon emissions — it is doubling down.

And due in large part to China, global coal power capacity under development increased for the first time since 2015.

At the same time, the EU and US are retiring coal plants rapidly as renewables, natural gas, and climate regulations make them less competitive, but they still need to speed up retirements in the coming years. According to a 2018 report by Greenpeace and the Global Energy Monitor, OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) member countries have to phase out coal completely by 2030 to stay in line with the Paris climate agreement goal to keep temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. The US and the EU — the world’s largest historical emitters — are not on track to retire their coal plants by that deadline.

“I hope people realize, it’s sad to say, but just how far off we are from where we need to be for the Paris climate agreement,” said Christine Shearer, program director at Global Energy Monitor and co-author of the new coal report.

China has pledged to go carbon-neutral by 2060, but its new coal spree is the latest sign that it is putting off the immediate actions needed to meet that long-term goal.

Understanding why China is still clinging to coal is critically important, because the country’s energy decisions over the next few years will play a decisive role in whether the world can meet global climate targets.

What’s driving China’s latest coal boom

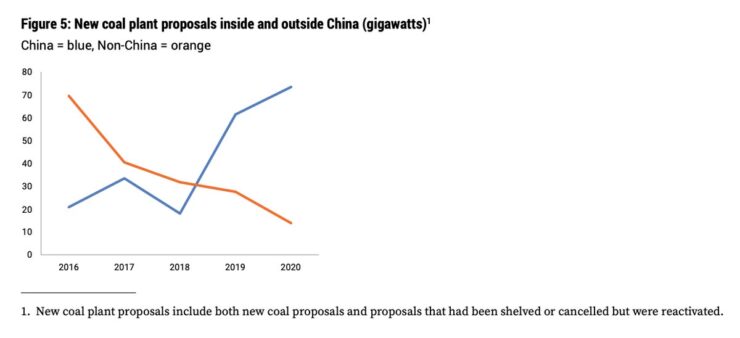

Over the past decade, China has been the primary driving force behind coal plant construction in the world. And in the last five years, that divide has grown. As the chart below shows, coal plant proposals have fallen rapidly in the rest of the world while climbing again in China since 2018.

http://www.sproles.com/test-01234/#comment-22487

https://www.autosaratov.ru/phorum/threads/490484-http-www-sproles-com-test-01234-comment-22487?p=8060018#post8060018

https://www.deviantart.com/xyzstreams/journal/Why-China-is-still-clinging-to-coal-878146047

https://greenwire.greenpeace.de/inhalt/freetvkentucky-derby-2021-live-streams-reddit-online

https://greenwire.greenpeace.de/inhalt/kentucky-derby-2021-live-stream-free-how-watch-online

https://greenwire.greenpeace.de/inhalt/live-tv-kentucky-derby-2021-live-stream-online-reddit-free-010521

https://greenwire.greenpeace.de/inhalt/watch-kentucky-derby-2021-free-live-stream-5121

In 2024, China added 38 gigawatts of coal-fired power — 76 percent of the global total — to its grid even as President Xi Jinping was calling for a global green recovery from the pandemic-caused economic recession.

Shearer said this construction was on par with previous years, adding, “It is surprising though, because for most countries there was a notable slowdown in 2024 due to Covid.”

How Biden could actually deliver on his climate goals

So why are we seeing such a big divergence between Xi’s growing climate rhetoric and construction on the ground?

The backstory is that China’s provinces were given the authority to approve new power plants in 2014, leading to a huge surge in projects. For poorer, coal-rich provinces, building a new power plant is a way to boost GDP. With the economic crunch from the pandemic, local governments launched a wave of new projects last spring, according to Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air, a global research organization.

China’s short-term climate target is just to peak its emissions, bringing them down before 2030; some government officials have taken that as a mandate to reduce emissions now, while “others see that as a window to build more fossil capacity while there is still space for emissions to grow,” said Myllyvirta.

However, local governments don’t have full autonomy over these decisions. The central government has maintained some control over coal plant approvals using a traffic light system, through which the National Energy Administration can place provinces under a red light, barring further coal plant development if they already have enough power capacity. In recent years, due to concerns about energy security as electricity demand continues to rise, the traffic light system has grown very lax, though.

To meet global climate targets, that system needs to change. “The concern is local government,” Fuqiang Yang, a senior adviser at Peking University’s Climate Change and Energy Transition Program, told Vox. “Now is the time for the central government to get back these approval rights.”

The central government has sent signals that it is cracking down on provinces pursuing new coal plants. China’s powerful Central Environmental Inspection Team made an unprecedented move in February, issuing a report condemning the National Energy Administration (NEA) for not prioritizing environmental protection in energy planning and allowing for unnecessary power plant development. But so far, the NEA hasn’t issued a public response outlining how it plans to change.

Meanwhile, another big test of the top authorities’ commitment to reining in coal is approaching. China released its 14th general five-year plan in March, and in the coming months, it is expected to release sector-specific plans including one for electricity development. The China Electricity Council has proposed a coal power capacity target allowing coal capacity to rise from 1,080 gigawatts in 2024 to 1,250 by 2025.

But that is not compatible with the Paris agreement. According to Yang, China will have to further limit coal capacity to 1,150 gigawatts to peak its emissions early, by 2025 (that peaking date is in line with the Paris 1.5°C target, according to the Asia Society Policy Institute). Greenpeace East Asia is lobbying for an even stricter 2025 target: 1,100 gigawatts.

Because China’s coal plants are being utilized far below their full capacity, climate advocates argue that further development isn’t necessary. But currently, China has 247 gigawatts of coal power under some stage of development, so meeting those stricter targets will be an uphill battle.

Building all that capacity could also create bigger hurdles down the line. According to Global Energy Monitor and Greenpeace’s 1.5°C coal phase-out pathway, China will need to start shutting down power plants by 2025, retiring 23 gigawatts annually through the decade. (And that report was written in 2018, before these latest coal power additions, so retirements will have to be even higher now.)

The rest of the world is turning away from coal, but not quickly enough

Outside of China, 2024 brought some signs of hope from regions rapidly moving away from coal and retiring existing plants, the new report found.

As the dotted line in the chart below shows, if you filter out China, coal retirements have been outpacing commissioning since 2018. (Commissioning refers to a plant that is built and ready for operation).

One big reason for that: a slowdown in coal development in India and Southeast Asia. “South-Southeast Asia was long regarded as the next hotspot of coal power after China, and instead what we are seeing is government after government there make announcements that they’re going to cut back the amount of coal plants they have planned,” said Shearer. The falling cost of renewable energy has made coal less attractive, and the drop in electricity demand due to the pandemic has given many countries an opportunity to reassess their energy plans, she said.

Global Energy Monitor

On the retirement side, the EU and the US are driving the trend, tying a record for global coal retirements last year. However, to actually follow the 1.5°C path — phasing out all coal plants in OECD countries by 2030 — the US, EU, and other major emitters need to make a much stronger push for early retirements in the coming years.

Even with these positive trends, China’s decision-making looms large, since the country currently accounts for half of the coal plants under development worldwide.