You’re a hero.”

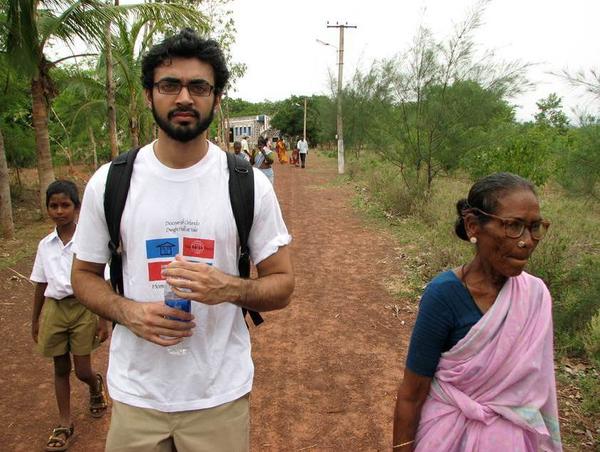

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard this from well-intentioned friends and family. They send messages of praise for the work I’ve done over the past decade, addressing rural health and infectious diseases in India (where I was born), Mozambique, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Thailand, Nicaragua, Rwanda and Uganda.

In many ways, this recognition felt and still feels misplaced.

I knew then and know now that the credit was far more deserved by my local health-care colleagues — many working in these areas their entire lives, not weeks or months. Unlike me, they didn’t always have a choice in the matter. And if something went wrong — like a global pandemic striking — many did not have the option to board a plane and fly out to somewhere safer. (To no surprise, the U.S. ended up being much less safe in the end.)

These local health workers cope perpetually with the lack of paved roads, limited sanitation systems, overt poverty and a host of deadly infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and dengue.

And now with the COVID-19 crisis, many of us in the West who work in academic global health have largely “stayed home.” In my own case, our health system restricted travel, including global health related work.

Our local colleagues are leading COVID-19 responses in their communities – lacking access to the life-saving vaccines that are being hoarded by our own countries. The same was true for ventilators, and the antiviral drug Remdesivir, earlier on.

This absence from our work in impoverished countries during a crisis is a humbling reminder of important realities for American and European global health practitioners. The work that we do in global health is often done at our convenience – if for any reason we opt not to go, impoverished countries and communities must continue the work either way. The work that to some of us is more academic is a matter of survival for residents of those communities. As my cousin in India once said, “Your global health experience is just another day in my life.”

Ultimately, some part of the U.S. and European participation in global health is just that: participation rather than equal partnership. Yet the power dynamics have for centuries leaned heavily and falsely toward the Western entity as the commanding leader— or more accurately, the brutal colonizer.

Crisis makes clear how wrong that is, because in an emergency, the response has been to leave rather than stay and help (there are some exceptions, such as Médecins Sans Frontiers or the American Red Cross, which specifically attend to crises).

The same Western exodus happened during the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as U.S. public health personnel were removed from areas of security concern and others were more significantly sidelined. In 2014, Donald Trump went as far as to tweet, “The U.S. cannot allow EBOLA infected people back. People that go to far away places to help out are great-but must suffer the consequences!”

More Than An Experience

But even though those who work in global health were sidelined by COVID-19, it was hard not to think about what would happen to our colleagues, friends and family in countries we work in outside of the U.S.

I thought about Rwanda—a country with a very strong health system, which averted any Ebola cases through strong public health monitoring efforts despite a large outbreak near their shared border. I had worked the eastern part of the country in a rural hospital in Rwinkwavu District in 2018—I thought of my friends in the villages that surround the hospital, where access to portable oxygen was limited, let alone access to the ventilators that so many of my Covid19 patients in Boston would end up on.

I also thought of my relatives in India — a far more densely populated country with more stark inequities in wealth and health. Born there and having worked in impoverished communities in the north and south of the country, I worried for the lives of both family and colleagues knowing that COVID-19 strikes most aggressively in these crowded conditions. India is now suffering yet another deadly resurgence.

Today, we are watching those colleagues struggle to get access to life-saving vaccines.

What’s Our Responsibility?

More than a year into the pandemic, I’m still pondering this question: What is our duty as American and European health-care professionals who work in global health during crises?

Advice To Parachuting Docs: Think Before You Jump Into Poor Countries

In an article on the ethics of pandemic response for a project that I led for the American Medical Association, the authors discussed the ethical obligations that American clinicians had to helping with international crises, including treating patients in areas with physician shortages that were outside our own borders. They argued that solidarity was a guiding force:

“The duty to care for those suffering on the other side of the globe may be strengthened by greater recognition of our shared vulnerability and a commitment to solidarity toward a shared threat.”

This quote signifies that our guiding principle in global health must be solidarity. If we are instead led by other forces—like academic advancement or international security—we will not succeed, and in the process do more harm.

And so for the past year, I leaned in to working on the Covid19 response here in my own state of Massachusetts, where we are plagued with similar inequities both in our hospitals and in our communities.

As an Indian-born, American physician, I am also trying to figure out what space I should and should not occupy in “global health.”

What I am sure of is that whatever I end up doing, it will be with the humility of sharing that space in solidarity with some of the real heroes around the world, including the doctors, nurses, community health workers and staff for whom COVID is but another crisis to which they have stepped up and fought back.